The role of computed tomography in detecting splenic arteriovenous fistula and concomitant atrial myxoma

29/04/2014

Screening & Beyond

17/09/2023Burr hole evacuation for infratentorial subdural empyema

Abstract

Core tip: It is general belief that subdural infratentorial empyema needs to be approached through an ample decompressive craniectomy. We present a case of infratentorial empyema managed successfully with burr hole evacuation of infratentorial empyema. We analyzed the characteristics of the case and reviewed the surgical techniques. Go to:

INTRODUCTION

Infratentorial empyema has been reported most frequently as a complication of middle ear or mastoid purulent infection. The neurological diagnosis may present with difficulties due to insidious development. However, it represents a serious condition necessitating prompt surgical evacuation. Suboccipital craniectomy is claimed to be the gold standard for the treatment of subdural empyema in the posterior fossa, aiming at brainstem and cerebellar decompression together with pus evacuation[1]. Go to:

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female was admitted to the department of infectious diseases with high fever, moderate headache, right ear pain, general fatigue and malaise. Right hypoacusia and neck rigidity was revealed at physical examination. One week’s dosage of oral amoxiclav before hospitalization was ineffective. A fundoscopy did not reveal any evident papillary edema.

In the absence of an intracranial hypertension, a lumbar puncture (LP) was done (November 3, 2006) and turbulent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was extracted. Laboratory examination revealed 8900 cells/dL, proteinorrachia 1.65 g/L. Blood test showed leukocytosis 25200, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 45 s within the first hour, hemoglobin 12.8 mg/dL. A computed tomography (CT) of the head excluded any mass occupying lesion. Despite the negative cultures of the CSF, the diagnosis of purulent meningitis was made and combined therapy was started with ampicillin 3.0 g four times a day (qid), amykacin 0.5 g twice daily (bid) and kemicetine 1.0 g thrice daily (tid).

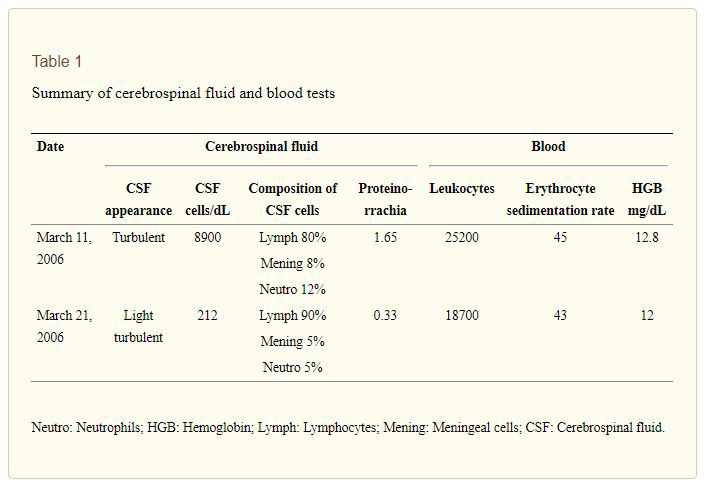

Another LP (March 21, 2006) revealed 212 cells/dL, proteinorrachia 0.33 g/L, lymph cells 90%, meningeal cells 5%, neutrophils 5% (Table (Table11).

Table 1

Summary of cerebrospinal fluid and blood tests

Neutro: Neutrophils; HGB: Hemoglobin; Lymph: Lymphocytes; Mening: Meningeal cells; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid.

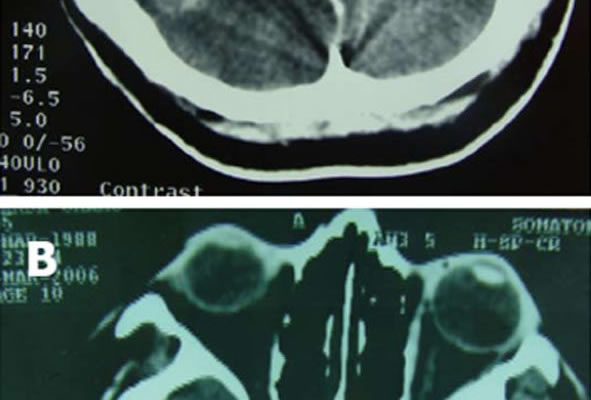

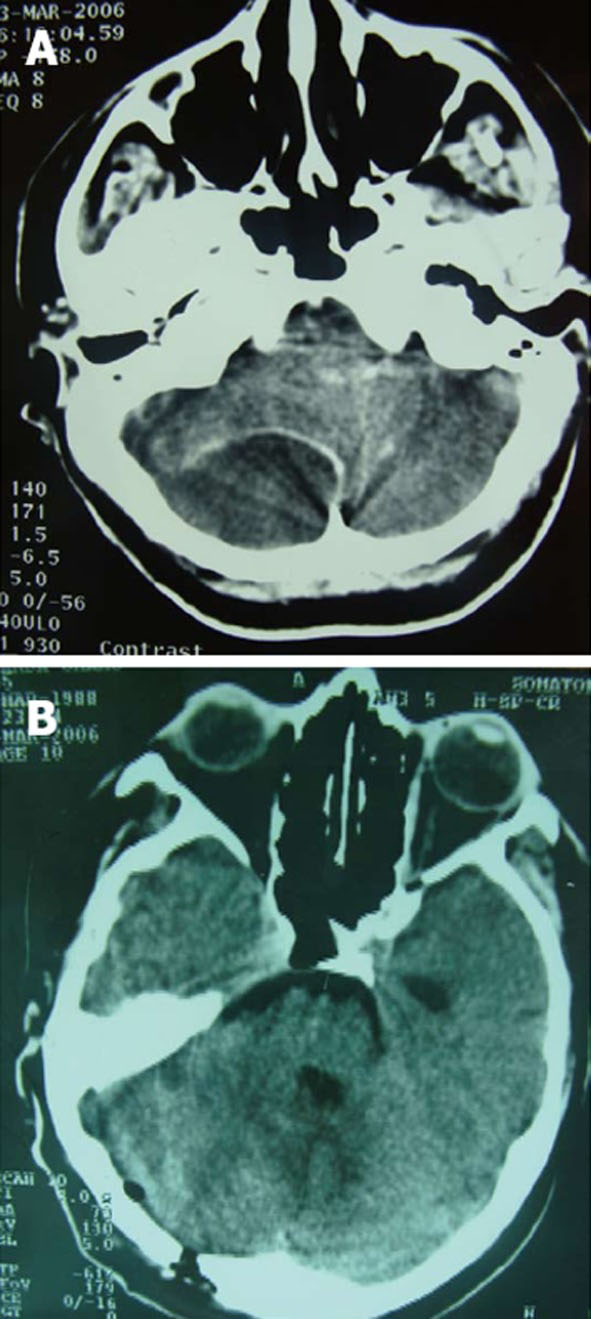

With combined antibiotic therapy, the headache, ear pain and neck rigidity improved until the night of March 22, 2006 when the patient presented with confusion, somnolence, neck rigidity, positive Brudzinski and Kernig signs and horizontal nystagmus. The next morning, the patient had a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 8 (E = 2; V = 3; M = 3). CT of the head with intravenous contrast injection documented right posterior cranial fossa empyema 6 cm × 5 cm compressing the right cerebellar lobe that appeared slightly edematous. There was compression of the fourth ventricle and herniation of cerebellar tonsils beyond the occipital foramen associated with three ventricular hydrocephalus. Right mastoid cells were opaque as in case of mastoiditis (Figure (Figure1A).1A). The patient was immediately transferred to neurosurgery for emergency evacuation of empyema. On admission, the patient was in coma GCS 5 (E = 1; V = 2; M = 2), with spontaneous extension of the head in the lateral recumbent position. Under local anesthesia with the patient in left lateral position with the head posed on the head support of the surgical bed, a 6 cm hockey stick incision over the right suboccipital area was made. A burr hole was drilled 2 cm on the right side and 2 cm under the right transverse sinus that corresponded to just in the center of the empyema. Dura mater was discovered attached to the inner layer of the bone without any extradural collection. The tip of a 20 F needle in a syringe was introduced through the dura and 22 mL of pus was withdrawn. At the end of aspiration, a small incision of the dura exposed at the burr hole was done. Cerebellar flocculi were visible without any space left for a catheter to be introduced in the subdural space for eventual drainage. The soft tissue around the

burr hole was rinsed with gentamycin and iodopovidone solution and closure of the wound was done. Intravenous vancomycin 1.0 g tid, ciprinol 200 mg tid was administered. Within one hour, the patient became conscious GCS 12 (E = 3; V = 4; M = 5) and the day after surgery was GCS 15. The culture exam showed no growth of microorganisms. Four days after surgery, the neurological status was normal except for the right hypoacusia. A control CT of the head in the third postoperative day showed complete evacuation of empyema, return of right cerebellar lobe to the normal position and reappearance in the midline of the fourth ventricle with resolution of the supratentorial hydrocephalus (Figure (Figure1B).1B). Right mastoid cells were still hyperdense. The patient was transferred to the department of otorhinolaryngology for the surgical treatment of mastoiditis. On March 27, 2006, the patient underwent radical right mastoidectomy under general anesthesia. Treatment with vancomycin 1 g tid, ciprinol 200 mg tid, flagyl 500 mg tid was administered until April 4, 2006. After that, ceporin 1 g daily was continued until April 10, 2006. The patient was discharged on April 22, 2006.

More than six years after surgery, the patient remains disease free and leads a normal life. She does not complain of hypoacusia on the right ear and refuses a control magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head.

DISCUSSION

Infratentorial empyema is a rare complication of bacterial infection of the middle ear or mastoid and constitutes only a small percentage of intracranial empyema. It is a life threatening condition due to its mass effect of direct compression to the brain stem and associated supratentorial hydrocephalus. Clinical diagnosis of infratentorial empyema is easily delayed due to its insidious onset and progression[2].

Clinical signs of infratentorial empyema were mostly absent, with lack of cerebellar findings and cranial nerve deficits in approximately 75% of the patients[2]. In our case, herniation of cerebellar tonsils manifested with head extension after the patient had already entered a stuporous state.

Most of the reviews on the subject advise an ample decompressive occipital craniectomy, especially in cases of extension of empyema to the cerebellopontine angle[1]. Ample decompression may serve for managing of cerebellar edema, even after pus evacuation, but it carries other risks, such as brain swelling, infarction or hemorrhage that may result from an injudicious aggressive opening of the dura[3].

In the presented case, there was no evident extension of the pus to the cerebellopontine angle. Furthermore, pus collection was limited to one side of the occipital squama without excessive cerebellar edema. Most of the mass effect seemed to be caused by empyema. We believe that the consequential three ventricular hydrocephalus was the cause of the comatose state. Spontaneous positioning of the head in extension came with the herniation of cerebellar tonsils in the foramen magnum. Our surgical choice was also influenced by the emergency for immediate evacuation of empyema. In such a situation, we adapted burr hole evacuation of empyema that reopened the fourth ventricle, resolving the hydrocephalus. Through a burr hole, we were able to drain the complete volume of empyema calculated in the CT, verified after the small dura opening that showed cerebellar flocculi, having reached the dura, leaving no space for a subdural drain. Intravenous perfusion with mannitol solution 20% and 15 degree upright position of the head were adapted to alleviate possible cerebellar edema and restore CSF dynamics. In their review, Bok et al[3] conclude that burr holes should not be disregarded as a method of treating subdural empyema.

The successful management of our patient demonstrates that a complete evacuation of subdural empyema can be obtained with equal efficiency through a single burr hole, as with other more invasive approaches such as craniotomy or craniectomy. The mass effect reduction after evacuation of pus was sufficient in our case to remove obstruction from the fourth ventricle and treat the hydrocephalus.

The combination of antibiotics was directed by clinical judgment since the culture study of pus and blood did not reveal any pathogens for a subsequent antibiogram[4]. Blood culture is reported to be sensitive in only 15% of cases[4]. Streptococcus pneumoniae has been known to

be the most common cause of acute otitis media, sinusitis and pneumonia and one of the most important causes of bacterial meningitis[5-7]. In critically ill patients, cefotaxime or ceftriaxone is most often the primary alternative[8]. Other alternative drugs include the carbapenems, newer quinolones, clindamycin, telithromycin, linezolid and vancomycin. Treatment guidelines often recommend the use of β-lactam/macrolide combinations as empirical therapy for patients with severe illness[8-10].

Mastoidectomy was done four days after empyema evacuation, with the patient neurologically recovered from coma. Combined surgical and medical treatment led to complete cure of our patient.

In conclusion, burr hole evacuation may be equally as efficient as other more invasive surgical approaches in the case of infratentorial empyema. This is true especially in the case of cerebellar convexity empyema without extension to the cerebellopontine angle. Once the mass effect of the pus is removed, resolution of hydrocephalus may be expected because of decompression of the fourth ventricle. Whenever complete pus evacuation is possible and there is a lack of extensive cerebellar edema in preoperative CT or MRI, such a technique may be the efficient approach for emergent treatment.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Bahl A, Habibi Z S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Lu YJ

References

1. Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, van Dellen JR. Infratentorial empyema: analysis of 22 cases. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1263–1268; discussion 1263-1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. van de Beek D, Campeau NG, Wijdicks EF. The clinical challenge of recognizing infratentorial empyema. Neurology. 2007;69:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bok AP, Peter JC. Subdural empyema: burr holes or craniotomy? A retrospective computerized tomography-era analysis of treatment in 90 cases. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] 4. Available from: http: //www.medscape.com/viewarticle/521337_2.

5. Austrian R. Some observations on the pneumococcus and on the current status of pneumococcal disease and its prevention. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3 Suppl:S1–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Austrian R. The pneumococcus at the millennium: not down, not out. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 2:S338–S341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Burman LA, Norrby R, Trollfors B. Invasive pneumococcal infections: incidence, predisposing factors, and prognosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, Mandell LA, File Jr TM, Musher DM, Fine MJ. Practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:347–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. BTS Guidelines for the Management of Community Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. Thorax. 2001;56 Suppl 4:IV1–IV64. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, Bass JB, Broughton WA, Campbell GD, Dean N, File T, Fine MJ, Gross PA, et al. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1730–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]